Located a couple of kilometers northwest of Pompeii, Boscoreale was buried following the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE. Different villas have been discovered and excavated at various points since the late 19th century, providing an unrivaled glimpse into aristocratic life in the countryside of Campania in the early 1st century CE. One of these villas—Villa della Pisanella—has provided us with a collection of 109 pieces of silver tableware that had been stashed in a chest and buried in a well. Most of the Boscoreale Treasure, as it is called, is currently on display in the Louvre.

Since its discovery, scholars have debated the identity of the woman. Suggestions have ranged from a personification of either Africa, Alexandria, or Egypt, to the legendary Cleopatra VII, the final ruler of the Ptolemaic dynasty of Egypt. Many scholars today have settled on Cleopatra Selene, daughter of Cleopatra VII and Mark Antony, as the best fit for its eclectic iconography.

What is the image of the daughter of Antony and Cleopatra doing on expensive Roman tableware? Well, in 31 BCE, Octavian (the future Augustus) defeated Mark Antony and Cleopatra VII at Actium. Pursued by Octavian, Antony and Cleopatra retreated to Egypt and committed suicide the following year. Cleopatra Selene and her twin brother Alexander Helios (~ 10 years old at this time) were taken back to Rome, where they were given into the care of Octavia, Octavian’s sister and the ex-wife of Mark Antony, who raised them in her household. In the mid 20s BCE, Augustus married off Cleopatra Selene to Juba II, his long-time friend and a Numidian prince. In 25 BCE, Augustus gave Juba the territory of Mauritania to rule over as king (ancient Mauritania was roughly equivalent to modern day northern Morocco and western Algeria).

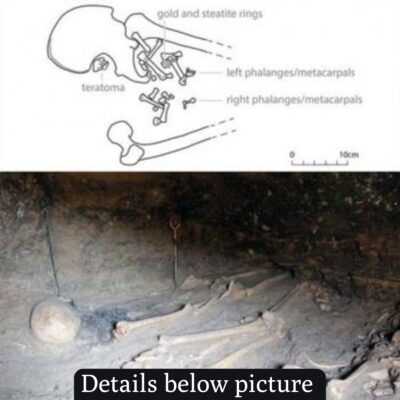

Images of a woman wearing an elephant scalp was the standard way of personifying Africa in Roman art (although the elephant scalp first shows up on the head of Alexander the Great, in the coinage of Ptolemy I). A woman wearing an elephant scalp shows up on the coins of Juba II, and is presumed to be Africa:

This is why the woman on the Boscoreale dish has traditionally been identified as ‘Africa’ (e.g., on the Louvre website). The argument for reading the Boscoreale dish as Cleopatra Selene, however, is that the portrait seems slightly more individualised in the representation of her features and not as idealised as one would expect for a goddess or personification (e.g., she has a very thick neck, which was a characteristic of Ptolemaic royal family portraits). The image could very well have been intended to evoke both, and the dish could have been commissioned to commemorate the marriage of Cleopatra Selene to Juba II and her subsequent elevation to Queen Cleopatra of Mauretania.