Nothing sticks in the mind quite like an unanswered question, such as a historic murder mystery, an unsettled death, an impenetrable enigma or even an ancient cold case just waiting to be resolved. A good detective eliminates the impossible, and whatever remains, however improbable, could just be the answer. Archaeologists are pathological problem solvers, obsessed with mysteries of the past. And nothing whets their appetite quite as much as the chance to put to use archaeological investigative techniques and tools from forensic archaeology in order to unravel the riddles of history. Join in the investigation as we solve some of our favorite cold case files.

Thanks to advances in technology, scientists have now uncovered new evidence in the cold case of Takabuti, the Egyptian mummy housed in Northern Ireland. (Ulster Museum)

Solving the Murder Mystery of Takabuti

Thought to be the first Egyptian mummy to reach Northern Ireland, according to The University of Manchester “there is a rich history of testing Takabuti since she was first unwrapped in Belfast in 1835,” as part of the mummy trade that followed the Napoleonic Wars. The hieroglyphs on her painted coffin provided experts with several clues as to her identity, namely that she was called Takabuti, lived in Thebes and was the wife or mistress of a noble. Takabuti is now housed at Ulster Museum in Belfast. 2,600 years after her death, advances in technology are allowing scientists to delve into her identity in new and unprecedented ways.

In January 2020, using CT-scans, carbon-dating, and DNA analysis, archaeologists made a breakthrough when they discovered that Takabuti had in fact suffered a violent death. In one fell swoop, research into the ancient mummy suddenly turned into an unsolved murder mystery.

Reanalysis in April 2021 revealed that not only had she had been stabbed in the back, but the fatal wound was inflicted by an axe, of a type commonly used by Egyptian and Assyrian soldiers. DNA analysis also uncovered her surprising genetic footprint, finding her DNA to be more similar to modern Europeans than to Egyptians. The plethora of information collected about this well-researched mummy has been included in a new book entitled The Life and Times of Takabuti in Ancient Egypt: Investigating the Belfast Mummy.

The discovery of remarkably well-preserved remains in Scotland allowed archaeologists to recreate the face of a Pictish man, brutally murdered about 2,600 years ago. (Christopher Rynn / University of Dundee)

Bringing Murdered Pictish Male Back to Life

A group of archaeologists excavating a cave in the Black Isle, Ross-shire in Scotland, couldn’t believe their eyes when they discovered the ancient skeleton buried in a recess of the cave. A bone sample sent for radiocarbon dating showed that the man died between 430 and 630 AD during the Pictish period. His body had been positioned in an uncommon cross-legged position, with large stones holding down his legs and arms

While the excavation provided no clues as to why the man was killed, the ritualistic placement of the remains did allow the archaeologists to learn more about the Pictish culture that buried him and inhabited parts of Scotland during the Late Iron Age and Early Medieval periods.

In order to unravel the murder mystery, the bones were sent to one of the most decorated forensic anthropologists in the world, Professor Dame Sue Black of Dundee University’s Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification (CAHID). Black verified that the “fascinating” skeleton was in a remarkable state of preservation and was able to describe in detail the horrific injuries the man had suffered.

The analysis concluded that he sustained at least five blows that resulted in fractures to his face and skull, allowing her team to understand how the man’s short life was brought to a violent and brutal end. Thanks to digital technology, scientists managed to successfully reconstruct the face of the Pictish man who suffered at least five severe injuries to his head, according to the BBC.

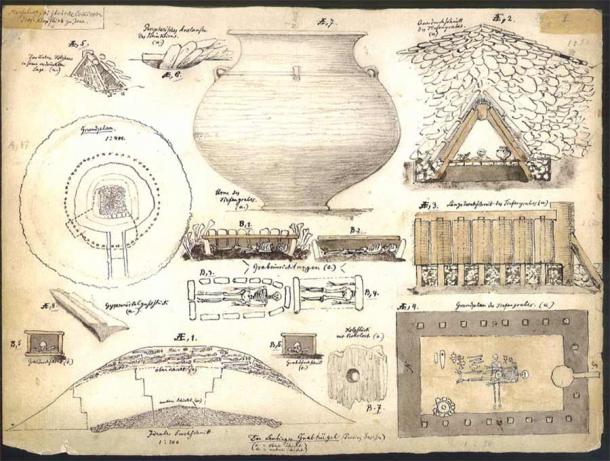

The remains of an early Bronze Age prince unearthed near Sömmerda in 1877 was the subject of the excavation diary kept by the archaeologist Friedrich Klopfleisch. (Fiedrich Klopfleisch / CC BY 3.0)

Uncovering a 4,000-Year-Old Politically Motivated Assassination

Almost 150 years after its first discovery, a team of archaeologists in Halle, Germany, reexamined the remains of the so-called Prince of Helmsdorf. The skeleton under analysis was that of a man discovered in the Leubingen mound in 1877, an Early Bronze Age grave located in the Thuringia region belonging to the Unetice culture.

The reason for revived interest in these human remains, which scientists suspected had suffered injury when doing inconclusive tests back in 2002, was due to the 1999 discovery by treasure hunters of the famed Nebra Sky Disk claims Smithsonian Magazine. “A sensational archaeological find,” according to Archaeology.com, this 3,600 years old bronze disk, inlaid with gold symbols, depicts a rich understanding of astronomical phenomena.

After a new book written by Kai Michel and Harald Meller was published about the enigmatic artifact, the need for forensic analysis was recognized in order to learn more about the mysterious human remains which were a product of the same culture.

In 2018, forensic experts identified what they deemed to be deliberate and lethal injuries. Frank Ramsthaler, deputy director of the University of Saarland Institute for Forensic Medicine, explained that these were probably caused by “a powerful and experienced warrior” stabbing the prince’s “stomach and into his spine.” All the evidence considered, author Harald Meller speculated that the unsuspecting ruler was “surprised by the attack.” The injuries found on his bones were seen as conclusive “evidence of the oldest political assassination in history,” continued Meller in DW.

Artistic rendition of the Koszyce burial showing kinship relationships between the victims in the cold case discovered in Poland. (Michał Podsiadło / PNAS)

5,000-Year-Old Brutal Family Murder Mystery in Poland

In 2011 a mass grave was discovered in Koszyce, southern Poland, by a team of Kraków archaeologists. Dating back 5,000 years, the mass grave contained the bones of 15 people, including women, teenagers, and small children – but only one man.

The scientists tested DNA from the 15 bodies and found that they were related, belonging to the Globular mphora culture which emerged in Central Europe around 3400 to 2800 BC. This meant that the archaeologists had stumbled across the remains of an ancient brutal family massacre. Polish experts suggested the family was executed during a ritual ceremony since the remains were found “lying close together, bodies and limbs overlapping,” claimed the paper published in PNAS.

While we might be shocked at such a dark discovery, the scientists called the find an “intriguing scene.” This is not because they are a tasteless bunch, but because murder mysteries like these allow them to test their skills. Bringing together several disciplines, including forensic archaeology, criminal anthropology and genome-wide analysis, archaeologists can use this technology to better understand not only how the group lived, but also how and why they died.

Artistic reconstructions of this mass grave found in Poland illustrate the entwined mass of bodies along with an analysis of their kinship relations. “Evidently, these individuals were buried by people who knew them well and who carefully placed them in the grave according to familial relationships,” highlighted the report. The archaeologists concluded that they may have been killed during a time of dwindling food stocks, which would explain why only women and children were found in the sacrificial pit.

Could these human remains really be evidence of a foundation sacrifice discovered in the Czech Republic? (Archaia Brno)

Unearthing Human Sacrifices Under Czech Medieval Castle

Back in 2020, archaeologists discovered the remains of three unfortunate victims at the 1,000-year-old Breclav Castle in the Czech Republic. Believed to have been murdered as part of a human sacrificial ritual, the human remains are thought to have been buried during the building of the castle in the early 11 th century, as their skeletons were found within the first layer of stones of one of the ramparts. The archaeologists even claimed that they could have been prisoners of war enslaved into building the stone walls before being sacrificed or executed.

If this all sounds a bit far-fetched, it’s important to note that the term “foundation sacrifice” actually exists, as certain medieval cultures believed that building a structure was an affront to the deities, and that to appease these spirits, sacrificial rituals were performed. These in turn created protective spirits that guarded the buildings in which they were entombed. According to a 1995 paper published in The Journal of American Folklore, all across the Balkans, ballads about foundation sacrifices are so renowned that variants of the tale have been embraced as part of national identity in countries such as Hungary, Romania and Greece.