Lamprey fossils are exceedingly rare, so these latest discoveries are helping scientists fill in an evolutionary gap between the fish that emerged 360 million years ago and those that swim in the world’s oceans today.

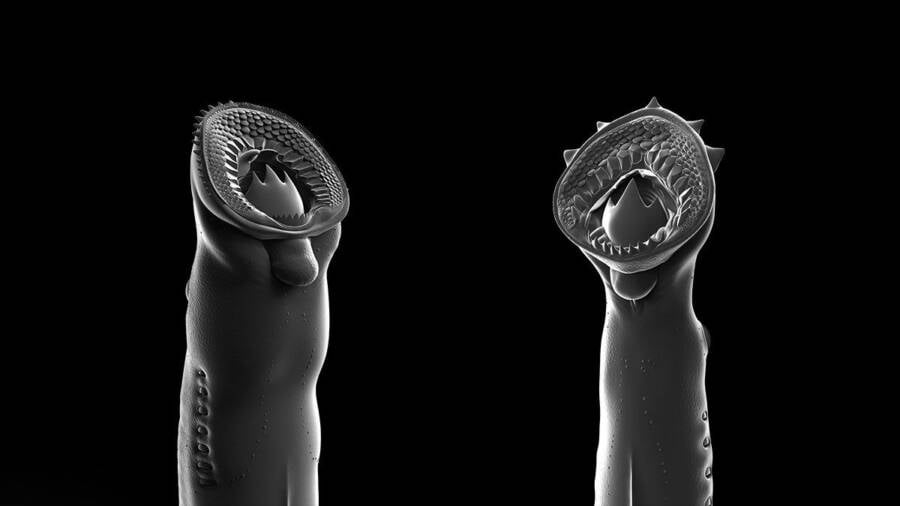

Heming ZhangThe newly discovered Jurassic lampreys had some of the most powerful “biting structures” among any known fossil lamprey.

Scientists in northern China recently unearthed two “exquisitely preserved” lamprey fossils dating back 160 million years. Now, they’re revealing new information about the evolutionary pattern of these bizarre creatures.

Lampreys have been around for 360 million years. The earliest species of the fish were just a few inches long and ate algae, but the fossils discovered at the Yanliao Biota rock formation were much larger. The jawless, eel-like creatures had “extensively toothed” mouths that they used to latch onto their prey, suck its blood, and even scoop off bits of its flesh.

“I was deeply impressed at first sight,” paleontologist Feixiang Wu told National Geographic.

Wu, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, discovered the fossils in a chunk of rock in Liaoning province. Each one reveals a different, previously-unknown species of the prehistoric fish.

Canadian Museum of Nature paleontologist Tetsuto Miyashita, who was not involved with the study, told National Geographic, “There have been no other lamprey fossils from the dinosaur age that preserve their terrorizing oral apparatus quite so clear.”

According to Miyashita, the fossil record for lampreys is “very sparse and poor.” But as Wu and colleagues noted in their study published in Nature Communications, “These fossil lampreys were exquisitely preserved with a complete suite of feeding structures.” This immaculate preservation allowed the paleontologists to gain a clearer picture of what lampreys were like 160 million years ago — and how they evolved.

Of the two newly identified species, Yanliaomyzon occisor was larger, measuring nearly two feet in length. It is the largest fossil lamprey ever found. This size is much closer to that of modern lampreys, which measure between 14 and 24 inches on average. Y. occisor was also several times larger than its earlier ancestors.

Heming ZhangYanliaomyzon occisor, the larger of the two ancient lamprey species, was about the same size as modern lamprey.

“Yanliaomyzon occisor, to our knowledge, the largest fossil lamprey known so far, ranks among the largest in modern species,” the study authors wrote. “Living lampreys’ adult body size is intrinsically related to their key biological features, with the larger and predaceous/parasitic species capable of migrating farther and achieving wider distribution, laying much more eggs, and being more tolerant to salt waters.”

Researchers believe the development of flesh-eating mouthparts may have played a large role in this increase in size.

As they noted in the study, “feeding opportunities” for smaller, ancient lampreys “were rather limited because the vast majority of their potential hosts then all had thick scales or armor.” Most likely, these early lampreys fed on algae, whereas most modern lampreys are predatory and parasitic.

There are non-parasitic modern lampreys, too, though they tend to be smaller freshwater species that don’t feed as adults. Instead, they “live off the reserves acquired as ammocoetes,” according to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

But the Yanliaomyzon fossils clearly took a different evolutionary trajectory from the lampreys that came before them. In addition to their larger size, the Y. occisor and Y. ingensdentes had mouths lined with sharp teeth and a structure known as a “piston cartilage” that helped them move their tongue. Wu noted that a modern species known as the pouched lamprey, which also feeds on the flesh of its prey, has a similar mouth structure.

“In the position of the intestinal tract, several tooth-bearing jaw bones and possibly skull bones of some unidentified bony fishes and some skeletal relics” were present, the authors wrote in the study. It’s possible that these ancient lampreys weren’t just capable of eating their victims’ flesh — they could also crush their skulls.

This evolutionary development may have been spurred by a larger change in other fish at the time. As Wu said, 160 million years ago, “bony fishes with thin scales began to abundantly emerge,” replacing the heavily armored fish that preceded them. For lampreys, this meant a new source of food, and they began to evolve into flesh-eating predators.

Given how incomplete the fossil record of lampreys is, these new discoveries are truly remarkable as they seem to come from a major turning point in their evolutionary history. While the full picture of lampreys’ evolution is far from complete, the discovery of these two new species certainly fills in what had previously been a rather large gap.