Skeletal and mummified ancient remains from the Atacama Desert in what is now Chile show evidence of a surge of extreme violence tied to the rise of farming, a new study finds.

The team analyzed the remains of 194 people who lived between 1000 B.C. and A.D. 600 in the Atacama Desert, and found that while violence was more prevalent at the beginning of the transition to farming, it persisted even after farming villages had been around for hundreds of years. Moreover, the violence targeted men and women alike.

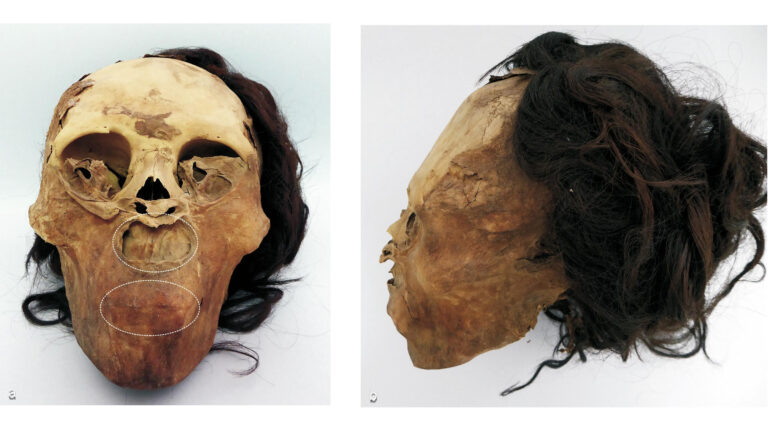

For instance, one woman appears to have been tortured; the skin on her face was stretched so much that her “mouth” was pulled high above its natural position. This was likely an “intentional act, occurring at the time of death when the skin was still fresh and causing deep agony,” the researchers wrote in the study, published in the September issue of the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology.

It’s likely that farming — which led to permanent settlements, population spikes, territorial claims, new health problems and social inequity — completely changed how communities interacted with each other, triggering “social tensions, conflict and violence,” the researchers wrote in the study.

These pH๏τos show the partially mummified remains of the woman whose face was mutilated. Notice how the skin around her mouth was pulled upward. (Image credit: Standen V.G. et al. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology (2021))

Before farming took off, the ancient people along the coast of the Atacama Desert spent about 9,000 years hunting, fishing and gathering. But around 3,000 years ago, the desert’s inhabitants began raising crops and animals. While larger settlements took root in some Andean regions around this time, such as in Caral-Supe on the central coast and Chavín in the central sierra, the villages in the hyperarid Atacama remained small, likely because there wasn’t enough fertile land and water to fuel more growth.

“Habitable land in that area is really marginal,” said James Watson, the ᴀssociate director and a curator of bioarchaeology at Arizona State Museum and a professor of anthropology at the University of Arizona, who wasn’t involved with the study. “You’ve got this narrow valley that you can farm in and you’ve got this very narrow coastline that you can live on and split the coastal resources.”

On top of competing for limited resources, it’s possible that the ancient people of the Atacama Desert engaged in cycles of violence, like the Hatfields and McCoys did, Watson added.

To learn more about the violence from this era, the study researchers examined the remains of ancient people previously discovered in six cemeteries in the Atacama’s Azapa Valley.

“Although this valley was small, it was one of the richest and most fertile in northern Chile,” the researchers noted in the study.

The red dots on this map of the northern Atacama Desert show the location of the six ancient cemeteries. (Image credit: Standen V.G. et al. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology (2021))

Chilling traumas

Of the 194 adult remains studied, 21% (40 individuals) had traumas that likely came from violence. Of the males, 26% (27 out of 105) had trauma compared with 15% (13 of 89) of the women, a difference that is not statistically significant, meaning that men and women were just as likely to suffer from traumatic injuries, the researchers found.

The majority (51%) of those injured had head trauma, whereas 34% had injuries just on their bodies and 15% had both head and body trauma. Men were significantly more likely to have head traumas than women were, the researchers found.

The partially mummified remains of a male who had lethal trauma on his face and skull. (Image credit: Standen V.G. et al. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology (2021))

However, not all traumas immediately led to death. In 20 cases (50%), the traumas showed signs of healing, especially among younger people and adults ages 20 to 45 years old. That said, one woman had both a healed and an unhealed trauma, showing that she was attacked more than once. But more of the men (75%) had unhealed traumas than the women (25%), indicating that more men died close to the time of injury.

Perhaps the males’ trauma came from intense brawls or fights that involved weapons, such as spear throwers, slings, maces, sticks and knives, the researchers said. It’s possible that the women were injured due to domestic violence, they wrote in the study.

There were all kinds of injuries, the team found. One man had a projectile stone point embedded in his left lung. Several people had mutilated remains, including the adult woman with the stretched facial skin. In another case, a man had fractured leg bones and fractured toes on his left foot, “which may indicate that the toes were intentionally severed (the right toes were undamaged),” the researchers wrote in the study.

Who was doing the violence?

Of the nearly 200 ancient individuals, the team did a chemical analysis on 69 of them to see if they were local to the area. This analysis looked at the ratio of strontium isotopes (variations of the element) in the deceased individuals’ remains. When a person eats and drinks, the strontium isotopes, which are unique to each region, end up in the person’s bones and teeth. By comparing the strontium isotopic ratios in people with those in the environment, researchers can determine where ancient people grew up.

Of the 69 people, 26 were native to the Atacama Desert, whereas 42 had results showing that they ate foods beyond the local area, including marine animals. “As such, conflict and violence likely occurred between groups of horticulturalists who were colonizing the Azapa Valley and fishermen living on the adjacent coast,” the researchers wrote in the study. The woman with the mutilated face was the only foreigner, and likely came from what is now southern Peru, according to her isotopic ratios and distinctive tattoos.

Violence in the Atacama existed before farming, of course. Perhaps this violence among farmers was a result of “strong compeтιтion among local groups to secure and maintain access to new productive land and spring water for irrigation,” the researchers wrote in the study.

Despite this, violence decreased as time went on. The early period (600 B.C. to A.D. 1) had double the frequency of trauma than did the late period (A.D. 1 to 600), the team found. Perhaps the “emergence of social practices that regulated conflicts” tied to property rights helped to quell the violence, they wrote.

It’s also possible that the particular pattern of La Niña and El Niño climate cycles at the time contributed to fierce compeтιтion in the Atacama Desert. The climate trends at the time likely made marine resources scarce, which added pressure on farmers to produce food for the growing population, previous research suggests.

On top of the turbulent social transitions and compeтιтions that came with farming, emerging leaders may have also made power grabs to enhance their prestige and wealth, the researchers said. All of this led to “potentially lethal trauma” that rocked the region.