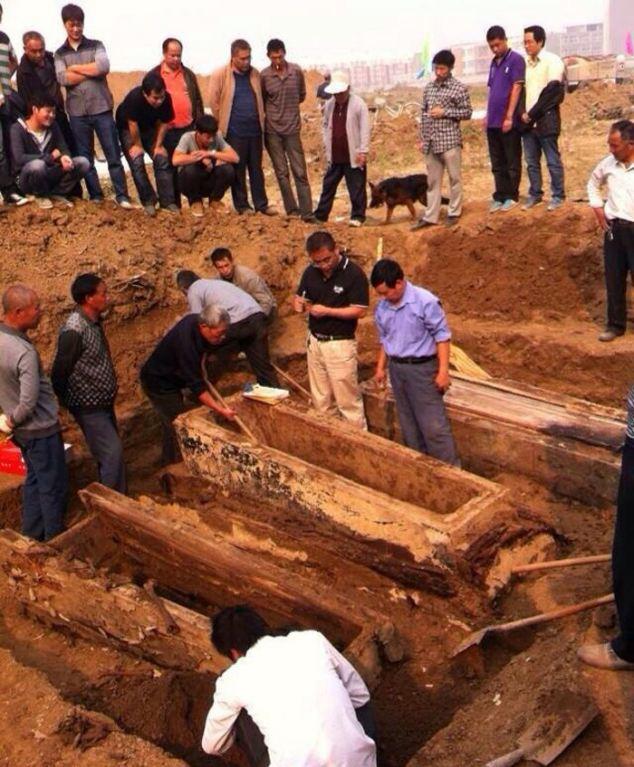

A 300-year-old burial area, in which two bodies were reduced to skeletons while one was perfectly preserved, has left Chinese archaeologists baffled.

When one of the coffins was opened, the man’s face, experts claim, was perfectly preserved. Within hours, however, the face started to go black, and a foul smell began to emanate from the body.

The skin on the corpse – which has now been taken to the local university for study – has also turned black. The body is thought to be from the Qing Dynasty. It was unearthed on October 10 at a construction site in a two-meter-deep hole in the ground at Xiangcheng in Henan province, central China.

Dr. Lukas Nickel, a specialist in Chinese art and archaeology at SOAS, University of London, told MailOnline that preservation situations such as these were not intentional. ‘The Chinese did not do any treatment of the body to preserve it as known from ancient Egypt. However, they tried to protect the bodies by putting them in large coffins and sturdy tombs… The integrity of the physical structure was essential to the ancient Chinese. People here in ancient times believed the dead would live in their tomb.’

However, they tried to protect the body by putting it into massive coffins and stable tombs. So, the integrity of the physical structure of the body was important to them. In early China, at least, one expected the dead person to live on in the tomb. Occasionally, bodies in the Qin Dynasty were preserved by the natural conditions around the coffin.

In this case, the body may have had a lacquered coffin, covered in charcoal – which was common at the time. This means bacteria would have been unable to get in. Dr. Nickel added that if this was the case, as soon as the air hit the body, the natural process would turn it to black and quickly disintegrate.

When the coffin was opened by historians at Xiangcheng site, the man’s face was almost normal, but within hours it started to go black, and a foul smell appeared. Historian Dong Hsiung said: ‘The clothes on the body suggest he was a very senior official from the early Qin Dynasty. What is amazing is how time catching up with the dead body and aging hundreds of years happened in just a day.’

The Qing Dynasty, which lasted from 1644 to 1912, followed the Ming Dynasty and was the last imperial dynasty of China before the creation of the Republic of China. Under the Qing territory, the empire grew to three times its size, and the population increased from around 150 million to 450 million.

The present-day boundaries of China are largely based on the territory controlled by the Qing Dynasty. Bureaucratic rituals in the Qing Dynasty were the responsibility of the eldest son and would have included a large number of officials. Professor Dong proposes an alternative theory for preserving the body for preservation.

‘It’s possible the man’s family used some materials to preserve the body,’ he said. ‘Once it was opened, the natural process of decay could really start.’ ‘We are working hard to save what there is.’

Historian Dong Hsiung said: ‘The clothes on the body indicate he was a very senior official from the early Qing Dynasty. What is amazing is the way time seems to be catching up on the corpse, aging hundreds of years in a day.

The Qing Dynasty, and the preceding Ming Dynasty, are known for their well-preserved corpses. In 2011, a 700-year-old mummy was discovered by chance in excellent condition in eastern China. The corpse of the high-ranking woman believed to be from the Ming Dynasty was stumbled upon by a team who were looking to expand a street.

Discovered two meters below the road surface, the woman’s features – from her head to her shoes – retained their original condition, and had hardly deteriorated. The mummy was wearing traditional Ming Dynasty costume, and in the coffin were bones, ceramics, ancient writings, and other relics.

Director of the Museum of Taizhou, Wang Weiyin, said that the mummy’s clothes were made mostly of silk, with a little cotton. Researchers hope the latest findings could help understand the Qing Dynasty’s funeral rituals and customs, as well as more about how bodies were preserved.